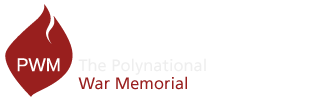

Holocaust Memorial: Architect Peter Eisenman, Berlin 2005

By: Sarah Quigley | posted: 9/21/2005 1:00:00 AM

One month before the much-debated Holocaust Memorial was due to open, the site was still in chaos. Berlin has a history of not finishing projects on time, and Eisenman’s Memorial looked like being yet another casualty. Workmen sat about looking exhausted while tourists peered curiously through the construction fence.

The building of the ‘Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe’ has been a protracted process. First proposed in the late 1980s, the project was not approved by politicians until the late 1990s, with American architect Peter Eisenman’s finalised design being presented to the public in 1999. Now, in 2005, here it was: an entire city block covered, seemingly haphazardly, in huge concrete blocks. Some of the ‘stelae’ lay low to the ground, while others stood upright, the tallest reaching a height of 4.7 metres.

The 2,711 pillars, planted close together in undulating waves, represent the 6 million murdered Jews. Both the subject matter (which has forced a taboo part of Germany’s past into public consciousness) and the site have raised controversy. The 19,000 square metre block of land, situated just south of the Brandenburg Gate, has a dark past. In 1937, it housed the office of Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels; nearby was Hitler’s Chancellery and the infamous bunker where he ended his life.

From 1961 onwards, the site lay alongside the Berlin wall, forming part of the no-man’s land separating Communist East from democratic West. As part of the GDR ‘death strip’, it was patrolled by guards and dogs, and monitored by cameras and trip wires. The Holocaust memorial, in contrast, has minimum security. Open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, it is accessible from all four sides. One of Eisenman’s primary aims has been to make the memorial an integral part of the city.

Although Berlin is one of the most tag-ridden cities in the world, the inevitable prospect of graffiti doesn’t worry Eisenman. ‘That’s an expression of the people,’ he says, with a shrug. The stones, however, have been given a graffiti-proof coating; and this in itself raised spectres from the past. In a stranger-than-fiction twist, the firm supplying the proofing was Degussa – co-owner of the company that made the Zyklon B gas used in concentration camps. By way of atonement, the company donated their product for free.

To the south-west of the site rise the ambitious buildings of Potsdamer Platz: glossy high-rises built in the optimistic early 1990s, with a stellar cast of international architects including Renzo Piano, Helmut Jahn, and Richard Rogers. With his memorial, Eisenman has not even attempted to compete with his neighbours, in size or material. Even on bright sunny days, the stones look sober and drab.

Standing on an uneven piece of land, the stelae almost fall into the centre of the site, rising up again towards the edge, forming a myriad of uneven stone corridors. Walking down one of these passages is disorientating, and scary; you can’t see who is approaching you, nor who is behind. The tilting ground and lack of vision offers some small idea of the Jewish experience from WWII: your past snatched away, your future insecure, little hope of escape.

Why Eisenman?

Memorials are now playing an increasingly important role in national conscience and international politics. Because of this, their construction has become an extremely controversial area of architecture.

Most war memorials from the twentieth century have been simply designed, and are simple in the emotions they raise. In cities, towns, and rural areas all over the world you can find pillars or columns on which are listed the names of locals who have died in various (mostly World) wars. Another construction commonly used for this purpose is the ceremonial arch.

There are a number of such ‘straightforward’ war memorials in Berlin. In the Tiergarten, close to the site of Eisenman’s project, is a huge construction topped by a stone soldier and flanked by tanks; this commemorates the 300,000 Soviet soldiers killed during the liberation of Berlin. In the former West stands the nineteenth-century Kaiser Wilhelm Church; smashed to pieces by Allied bombs, its ruins have been kept as a reminder of war, even while a new church and glass tower have been constructed beside it.

But newer memorials, commissioned from international architects and involving large budgets, often raise heated debate, particularly in a newly bankrupt Berlin. Libeskind’s New Jewish Museum was one such minefield: burdened by the necessity of doing justice to an unbearably weighty past, it opened well behind schedule in 2001. In a strange coincidence, the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center occurred just hours before the official opening of the Jewish Museum; and subsequent reconstruction at Ground Zero has been stalled for similar reasons: conscience, guilt, and the complicated issues that surround all symbolic architecture.

With the Holocaust Memorial project Eisenman (like Libeskind) has gained a kind of credibility stemming from his Jewish background. Born in 1932 to non-practising Jewish parents, he has always asserted that his origins have little impact on his architecture. During work on the Memorial, however, he admitted to a personal investment. ‘[With this work] I came back to the heart of my identity,’ he says.

Protests against the Memorial – both its concept and design – have been numerous. In 1999, the German parliament voted 325 to 218 (8 members abstained) to dedicate the Berlin memorial only to the murdered Jews of Europe. In the eyes of many people this means a neglect of all other victims of the Nazi regime, such as homosexuals, conscientious objectors, and Gypsies. Jewish communities have queried the relevance of the plain design: no stars or other insignia have been included, nor any victims’ names.

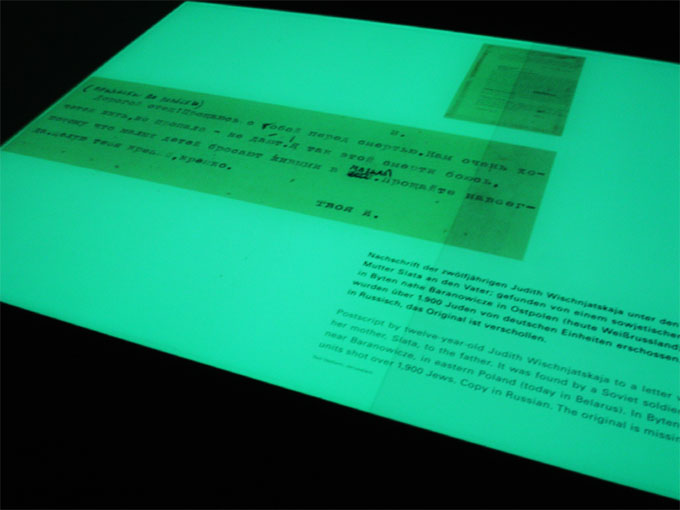

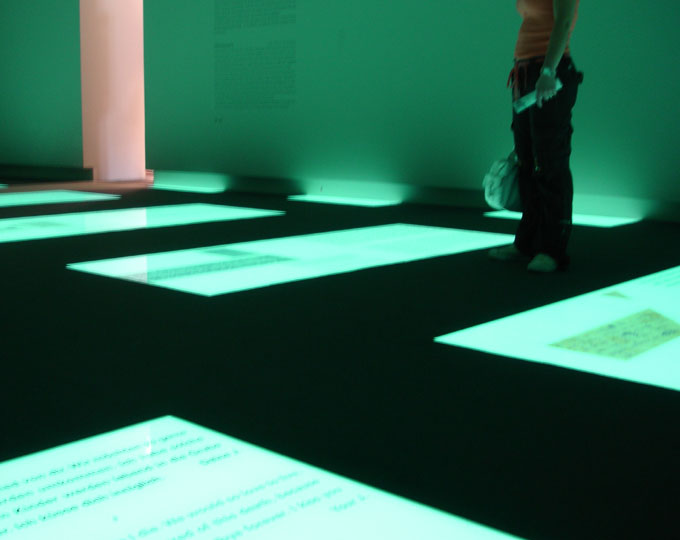

After Eisenman’s designs were made public, several prominent Germans, including the writer Günter Grass, urged the government to reconsider, criticising the Memorial as oppressive and overly abstract. Partly as a response to this, an underground information centre has been built, which provides visitors with historical facts and a context otherwise lacking.

But Eisenman remains adamant that the memorial is both perfect in its symbolism, and a necessary aid to atonement. ‘It stands there, silent,’ he says: ‘the one who has to talk is you.’

Endings, and a new future

The opening was carefully timed to take place on 10 May, two days after the 60th anniversary of VE Day. It was a charged political setting in which to stage the event, and in the final days of construction the weather was equally unsettled. As the last cobblestones were laid, and a temporary media pavilion was erected on the southern edge of the site, hail flew. Water lay on the stones like broken glass. It seemed a fitting atmosphere for a project whose completion had taken seventeen stormy years.

Even at the ceremony, which was attended by Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, Parliamentary President Wolfgang Thierse, Jewish delegates, and more than 500 international journalists, the project – which had now cost over 27.6 million Euro – raised controversy. Paul Spiegel, the head of Germany’s Central Council of Jews, pronounced that it remained ‘incomplete’, in its failure to force confrontation with the past.

Yet this was perhaps one of the best possible endorsements, for all along Eisenman has aimed to open up discussion rather than close it off: that is, to take the Memorial beyond its specific Holocaust context, and raise wider issues of anti-Semitism and social responsibility. In this, undoubtedly, his abstract design has worked.

‘I think people will eat their lunch on the pillars,’ he said. ‘I’m sure skateboarders will use it. People will dance on top of the pillars. All kinds of unexpected things are going to happen.’

© Sarah Quigley 2005

Photos © Jon Brunberg